The story of a long lost sea and an island

The Pannonian Sea and Papuk

Millions of years ago, Croatia looked very different from today; a large inland sea lay over the northern and eastern part of the country, the Pannonian Sea. With this storymap, you’ll better understand the journey and history of this vanished sea.

Starting with the origins and disappearance of the sea, in the section The Lost Sea. The story then continues to tell you about Papuk―today a mountain, but once an island in this sea. Traces of the Past tell the story of the marine life at that time, while Sites that tell the story show where in Park you can still find old unique geological features from this time. From Sea to Geopark describes the preservation efforts and its effects on geological heritage. And Dive into the Sea gives a brief intro of what’s to see at the House of the Pannonian Sea, where you can go and experience more of this vanished sea. Lastly, there are the Credits and Sources that link back to the original sources for transparency.

Together, these chapters tell the story of a vanished sea and the island of Papuk, which have shaped the current landscape and give unique insights in the geological history of the Slavonia region.

The Lost Sea

Covered by the flat plains of today across Central-Europe, there lies an untold story. Many millions of years ago, there was a large inland sea—The Pannonian Sea—that supported a wide variety of marine life. Over the course of its life this Sea became increasingly smaller until it fully disappeared. But even today, its legacy remains in the landscape and fossils beneath our feet. To understand its history, we need to go back in time.

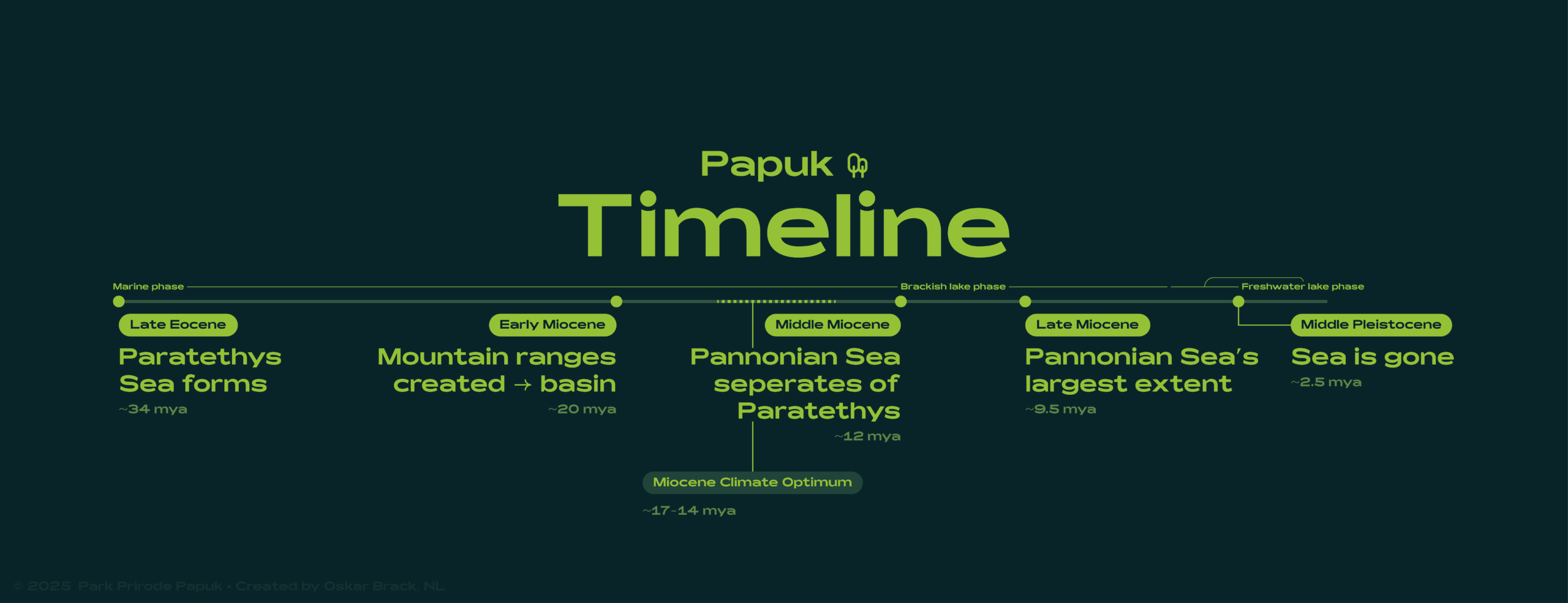

Timeline showing key events of the Pannonian Sea ⁕ ©2025 Oskar Brack

Back in time

Far before the Pannonian Sea even became to be, it was a part of a much larger sea, the Paratethys Sea. It formed about 34 million years ago due to tectonic movements that separated it from the ocean Tethys. Once formed it covered a massive 2.8 million km² that ranged from the modern-day Eastern-Alps all the way to Kazakhstan. Due to the fact that there was a limited connection to the Adriatic Sea (connected to the Mediterranean Sea), the water in the Paratethys Sea had a salinity of 12-14%. Usually seawater has a salinity of 3.1-3.8%.

The Paratethys Sea was connected to the Mediterranean Sea near present-day Trieste in Italy. Over time the ever-growing mountains caused the basin to be cut off from the open sea and turned this sea into a Megalake with a volume of 1.7 million km². It caused the Marine Phase to come to an end, and started the Brackish Lake Phase, as it became less and less salty. ~2 million years before it disappeared, it even reached the Freshwater Lake Phase.

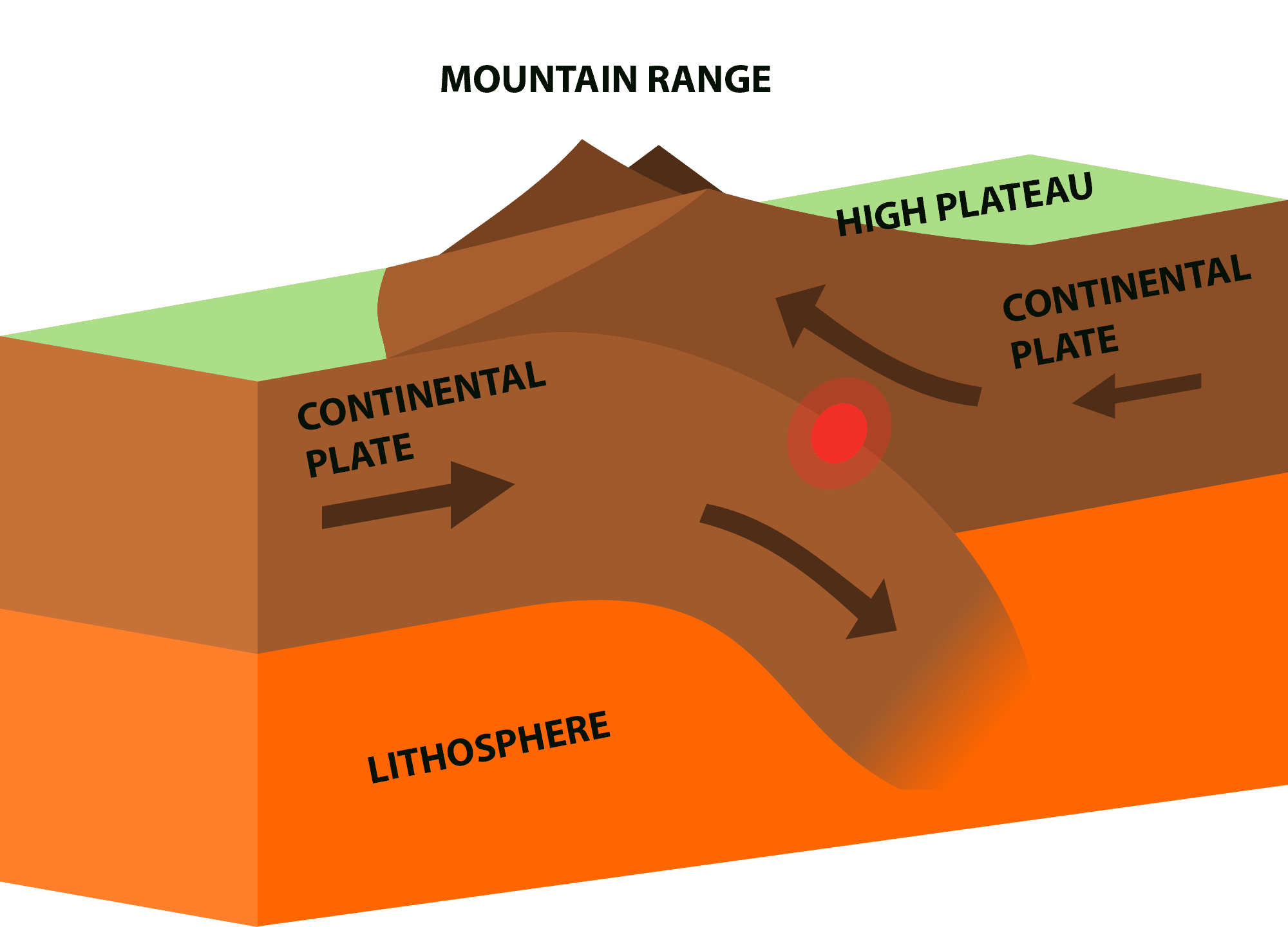

A basin was formed

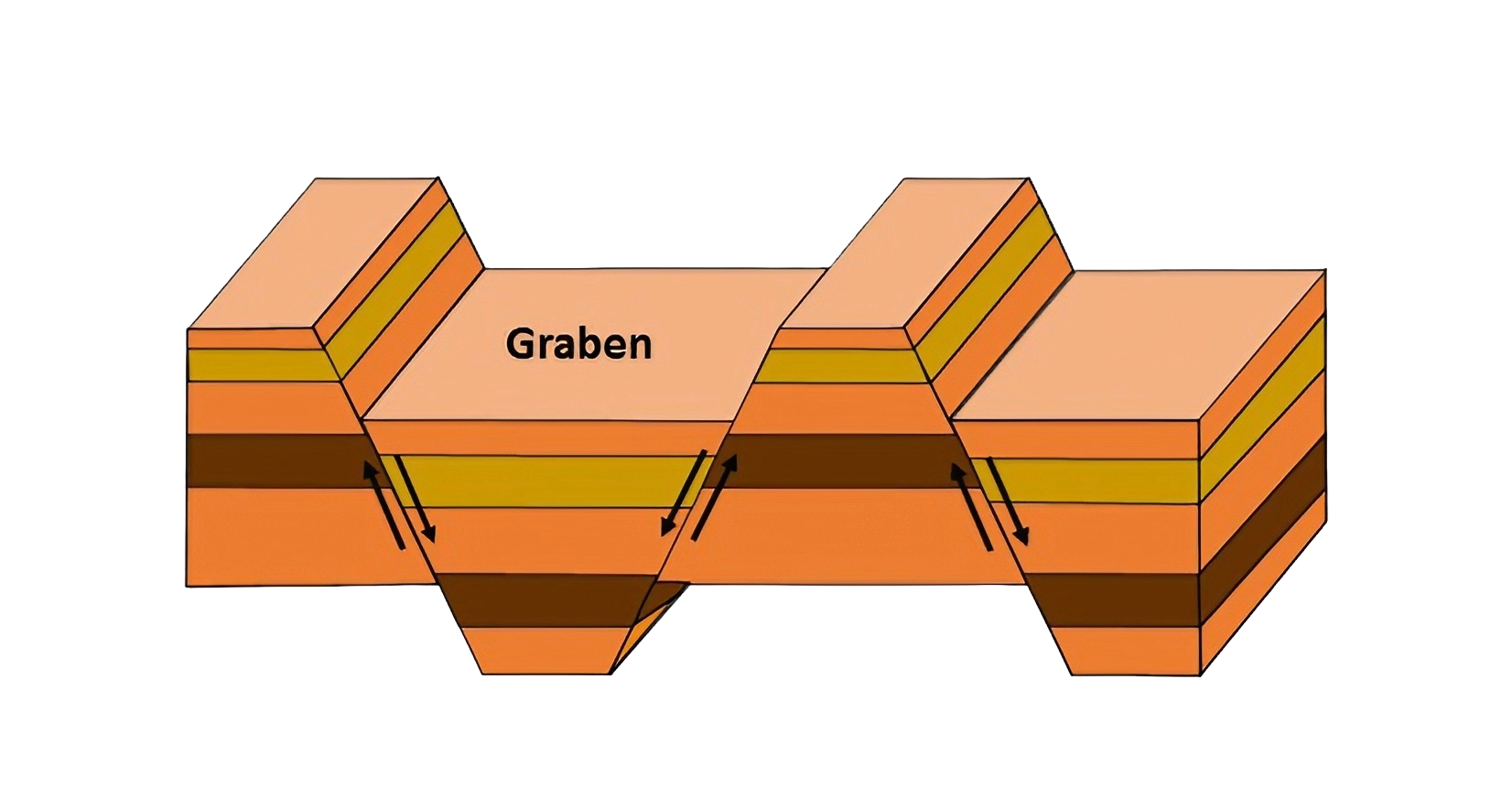

Roughly 20 million years ago, the earth’s plates in Central Europe were on the move, and the African plate and Adriatic so-called ‘microplate’ pressed against the Eurasian plate. These movements caused the uplift and creation of mountains; today’s Alps, the Carpathians and Dinaric Alps. At the same time it caused land behind those mountains to sink, creating a large bowl with high edges―symbolised by mountains. This process is called ‘horst’ (parts that rise) and ‘graben’ (parts that sink), and is caused by the earth’s curst cracking when big, hard blocks of rock are pushed by tectonic plates and the pressure builds up too high.

Specifically near the Papuk area, an old and strong block of crust made of rocks like schist and granite rose, while the land around it sank down and formed a geological basin where water began to assemble—the Pannonian Basin.

Step 1

While the mountains were rising, the land behind them started to sink. The ground was stretched and pushed down by the same powerful tectonic forces, causing it to bend inward and form a huge, bowl-shaped valley; a so-called ‘back-arc basin’.

Step 2

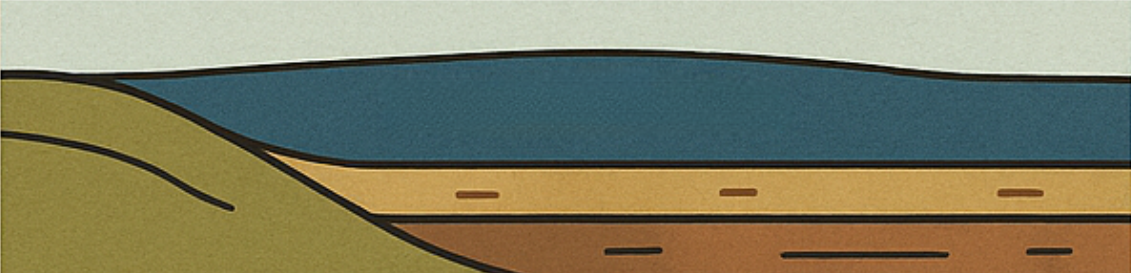

Illustration of geological formation of the Pannonian Basin ⁕ ©2025 Oskar Brack

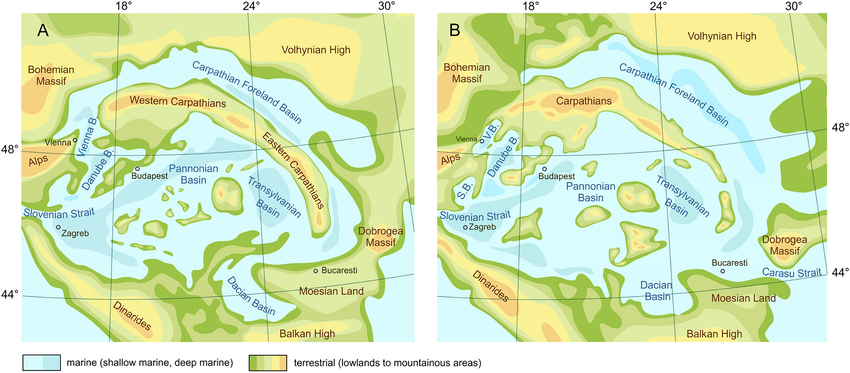

In the Middle Miocene-period, the Pannonian Basin was a part of the Central Paratethys; a semi-isolated sea that stretched across much of Central- and Eastern Europe. At the time of the MCO, it was also connected to the Eastern Paratethys, so marine waters dominated the region as the Eastern Paratethys was essentially a giant sea.

The Central Paratethys existed until the Middle/Late Miocene boundary―after which the area was transformed into the brackish Lake Pannon that gradually filled with river sediments that had flowed into the lake during the Pliocene.

The surrounding mountain ranges, such as the Alps and the Carpathians, continued to rise. Simultaneously global sea levels were fluctuating in a natural rhythm of warm and cold periods. During colder periods sea levels dropped, causing shallow connections between parts of the Paratethys to disappear. In warm and dry phases evaporation rates started to increase significantly. In certain sections the water level has dropped so much that entire sections of the lake dried out. As a result of these two things the Paratethys Megalake gradually reduced to increasingly more isolated inland seas, one of which was the Pannonian Sea. It then started to behave like a separate inland sea, with no connection to other seas.

At the time of its separation from the Paratethys, around 12 million years ago, the Pannonian Sea covered a large area in Central Europe. When it was at its largest size ~9.5 million years ago, the Pannonian Sea covered large parts of present-day Croatia, Slovakia, Serbia and Romania, plus almost the entirety of Hungary. It even reached a little part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Czechia, Austria, Slovenia and Ukraine. The total lake cover-area was an impressive ~250.000km², measuring ~500km wide and ~600km long.

Originally the water in the Pannonian Sea was salty, but after losing its connection to the ocean, that began to change—albeit slowly. Over the course of millions of years, it had slowly turned into a brackish lake by rain and rivers flowing into the Pannonian Sea, diluting the salt in the sea. Since this was a time of average cooler temperatures there was less evaporation, so the salt didn’t build up all that much. On deeper parts it was a little saltier though.

View the video below to see the sea change in size and water type:

Transformation of the Pannonian Sea over time ⁕ ©2025 Oskar Brack | Extent interpretation based on: ©1999 Magyar et al., ScienceDirect | Artificially generated voice by Canva

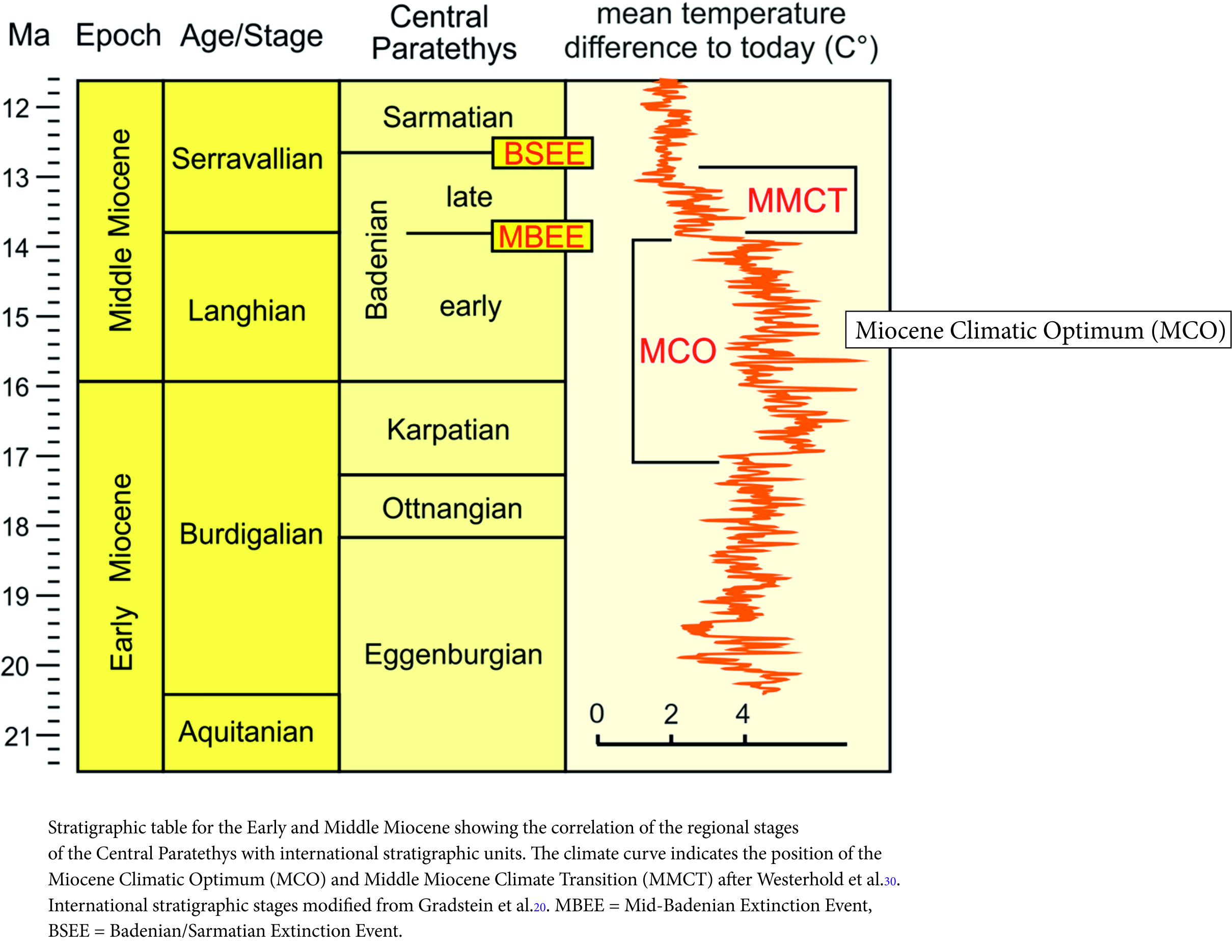

The climate

Unsurprisingly, after briefly mentioning it previously, the climate also had a big influence on the size of this Sea. About 17-14 million years ago, the earth experienced a period of global warming called the Miocene Climate Optimum (MCO).

During this period of time, global temperatures were about 3-6°C warmer than today. The warming didn’t happen all at once, but gradually over hundreds of thousands of years; creating a long period of stable, warm, and humid conditions. In Central Europe this meant milder winters, even warmer summers and increased rainfall throughout the year. And these temperatures also caused the rivers towards the basin to flow more strongly—carrying large amounts of freshwater, diluting the Pannonian Sea even more.

At the beginning of the MCO (during the Karpatian stage), this warming led to a (sub)tropical climate within Croatia’s Slavonia-region, as can be proven by plant fossils that have been found in the southern slopes of Papuk UNESCO Global Geopark, near the small village of Poljanska.

Plants like the cinnamon tree (see image on the right) would not be able to survive in the present-day climate, but thrived during the Miocene Climate Optimum. The land was covered in dense and lush vegetation, including swamps, forests and wetlands, which created a habitat for crocodiles, turtles and even elephants and rhinos to feel at home.

Due to the increasing air temperatures, the MCO also influenced the formation of the Pannonian Sea—during the Badenian stage. Seawater rose to subtropical levels, supporting (sub)tropical fishes and marine mammals, including whale-like creatures. So the Pannonian Sea was full of life—both in the water and on land. Numerous fossil discoveries prove the existence of this once vibrant (sub)tropical environment.

Around the edges of the lake, the earth was geologically active. While there were no actual stratovolcanoes, the earth’s crust was so thin around this area that magma could easily flow to the surface via cracks in the ground. Volcanic material like lava, ash and gases leaked out and since this volcanic activity continued for a long time, the lake ended up diluted quite a lot with volcanic waste.

The Vanishing Sea

While these volcanic activities were ongoing and through volcanic rocks into the sea, the rivers kept carrying mud, sand and stones into the sea. All these materials sank to the bottom and slowly started to fill up the lake, and step by step the water got shallower. The Pannonian Sea, once full of water and life, started to disappear.

So these rivers once made the Pannonian Sea as big as it was, but they also caused it to vanish slowly.

Step 3

Step 4

Over time, this buildup of sediment made the lake shallower and smaller. By the end of the Pliocene (2 million years ago) the lake had completely been filled―marking the end of the Pannonian Sea.

Illustration of the geological process of the filling of the Pannonian Basin ⁕ ©2025 Oskar Brack

Your Content Goes Here

The island Papuk

When the Pannonian Sea was still a vast inland sea, it is likely that a chain of ancient mountains—the so-called insular mount-ains—usually stood out above the surface like islands, including Mount Papuk. Unlike the surrounding landscape, these islands resisted the layers of sedimentation that filled the basin slowly.

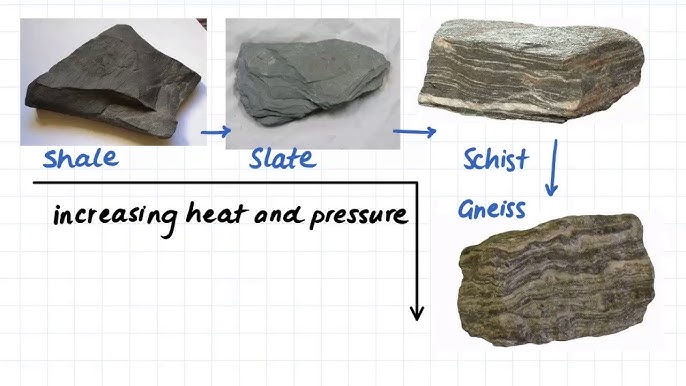

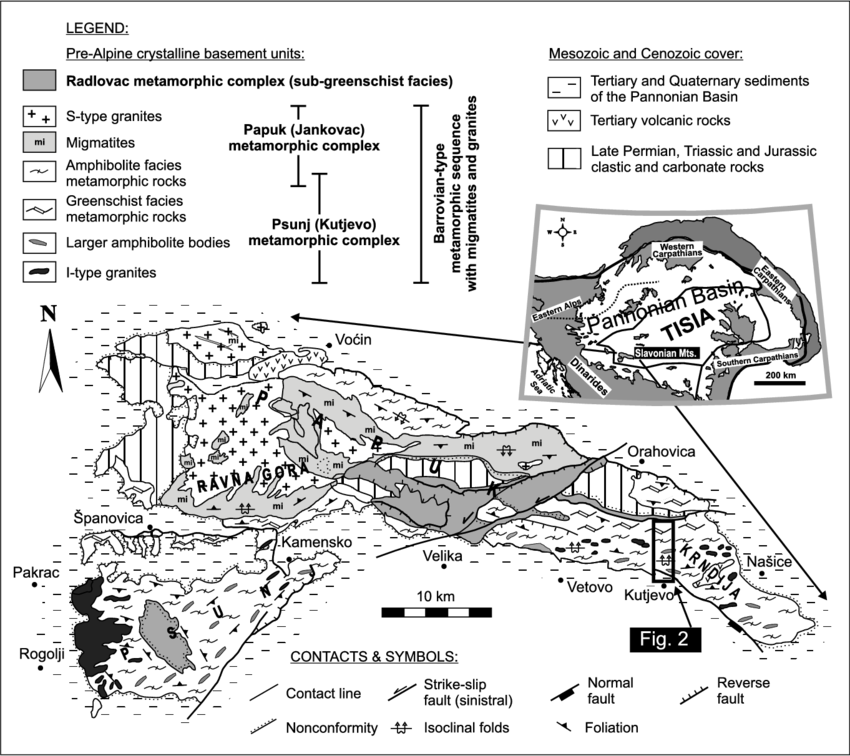

Old rocks are the roots of this ancient mountain—formed by ancient forces over ½ billion years ago during the Cambrian period. It has successfully survived the test of time due to intense heat and pressure that transformed sedimentary and volcanic rocks into metamorphic rocks far beneath the surface. Under immense pressure, metamorphic rocks like gneiss, schist and quartzite were created.

Shaping Papuk

Advancing hundreds of millions of years, enormous tectonic forces caused the rocks underneath the nowadays Alps to fold and crumple―also known as the Alpine orogeny, where two tectonic plates―the African and Adriatic plates―pushed against the Eurasian plate with such as pressure that not only the Alps formed, but actually the Carpathians and Dinarides too. It has reshaped large parts of Europe; including the land that one day would become Papuk.

Once the pressure had stopped, the earth’s crust began to stretch and crack—a process that is known as extension, and is a usual geological phenomenon after the being folded. As the crust stretched, it broke along deep fault lines; allowing blocks of land to move vertically. Some blocks rose to form ‘horsts’ (raised ridges), while others sank to form ‘grabens’ (low-lying valleys). It created the horst-graben structure that’s spread over the entirety of the Pannonian Basin.

While surrounding areas sank and filled with younger and softer sediments, the block on which Papuk lies (a horst) was uplifted in the Pliocene—during the latest tectonic phase, 5 to 2.6 million years ago. What’s visible at the surface now, at some point in time was the Basin’s seafloor/basement. It is also likely that Mount Papuk occasionally looked like an island, when in reality it was just a peak.

Years pass (millions), and the land moved again and new layers are added too. In the Miocene-period—when the whole area was covered by the Pannonian Sea—sand, mud and shells settled at the bottom and turned into softer rocks like sandstone and clay.

But simultaneously, the earth’s crust weakened in some places due to the stretching and thinning of the Pannonian Basin. Using these thinner zones, magma from deep inside the earth was able to rise to the surface. It cooled and hardened in basalt once it reached the surface, creating unique basalt rock formations like Rupnica.

When everything had settled again, nature came with another challenge: earthquakes, making the mountains shook, causing landslides that formed new layers with a mixture of broken rock and mud. Over millions of years, these layers built up, shifted, and sometimes even eroded away again.

Simplified geological map of the Slavonian Mts. ⁕ ©2006 Péter Horváth, ResearchGate

While a lot of research has already been done, it is still not entirely understood how the Slavonian Mountains (including Papuk) formed. It will require more research which will most certainly follow in the future, but what we know for sure already today: rocks that don’t match one another in a geological timeframe are exposed at the surface together, indicating special events. So these rocks don’t simply tell how the land was shaped, they also hold traces of a long-gone past.

Traces of the past

Let’s explore some of these traces of a long-gone past.

During the time of the Paratethys Sea (and later the Pannonian Sea too), deep parts in these Seas were often low in oxygen, leading to a slower decomposition of organic material—leading plant and animal remains to decay very slowly. It were ideal conditions for fossil formations, where these remains were buried in the sediments. It gives us a unique look at the biodiversity and ecology from that time.

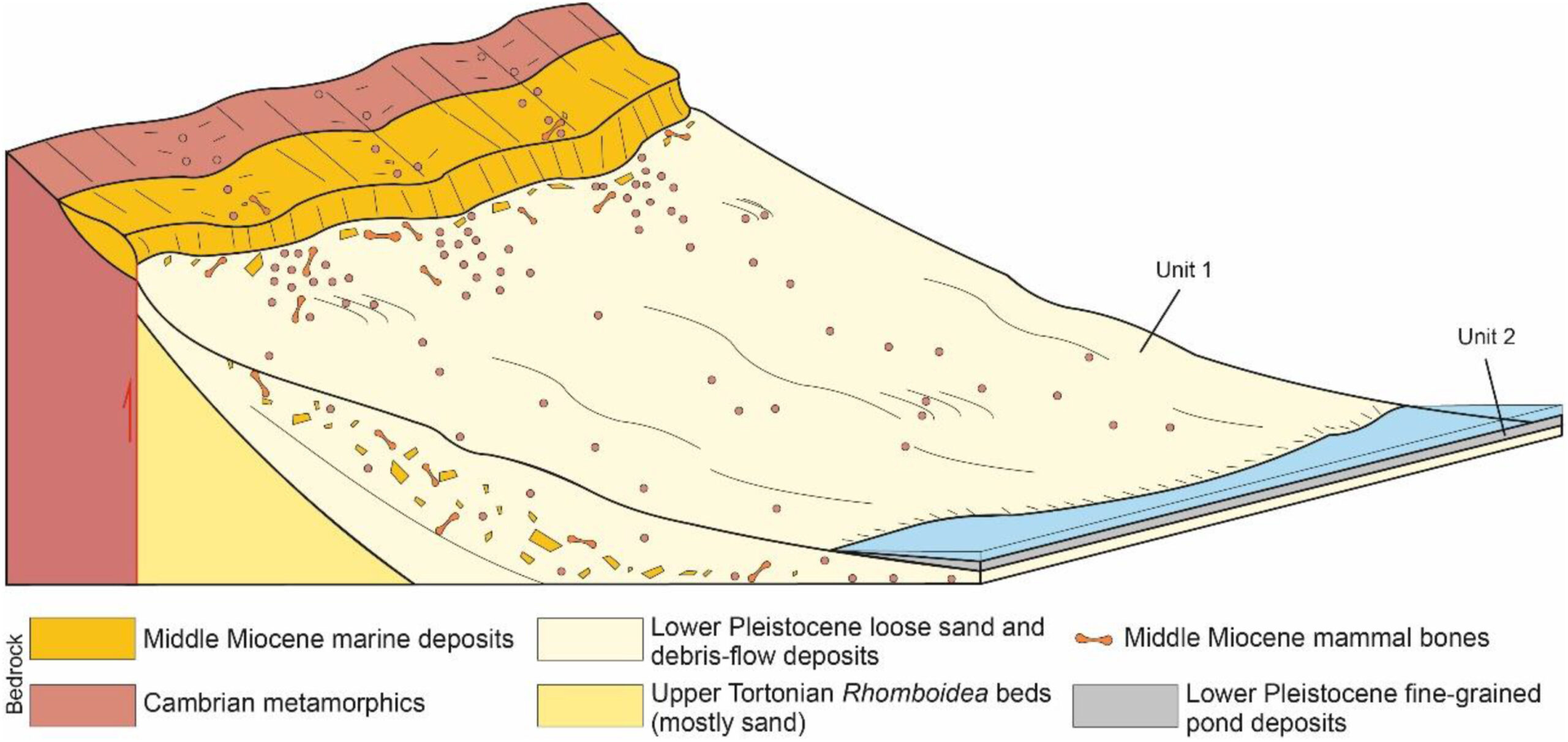

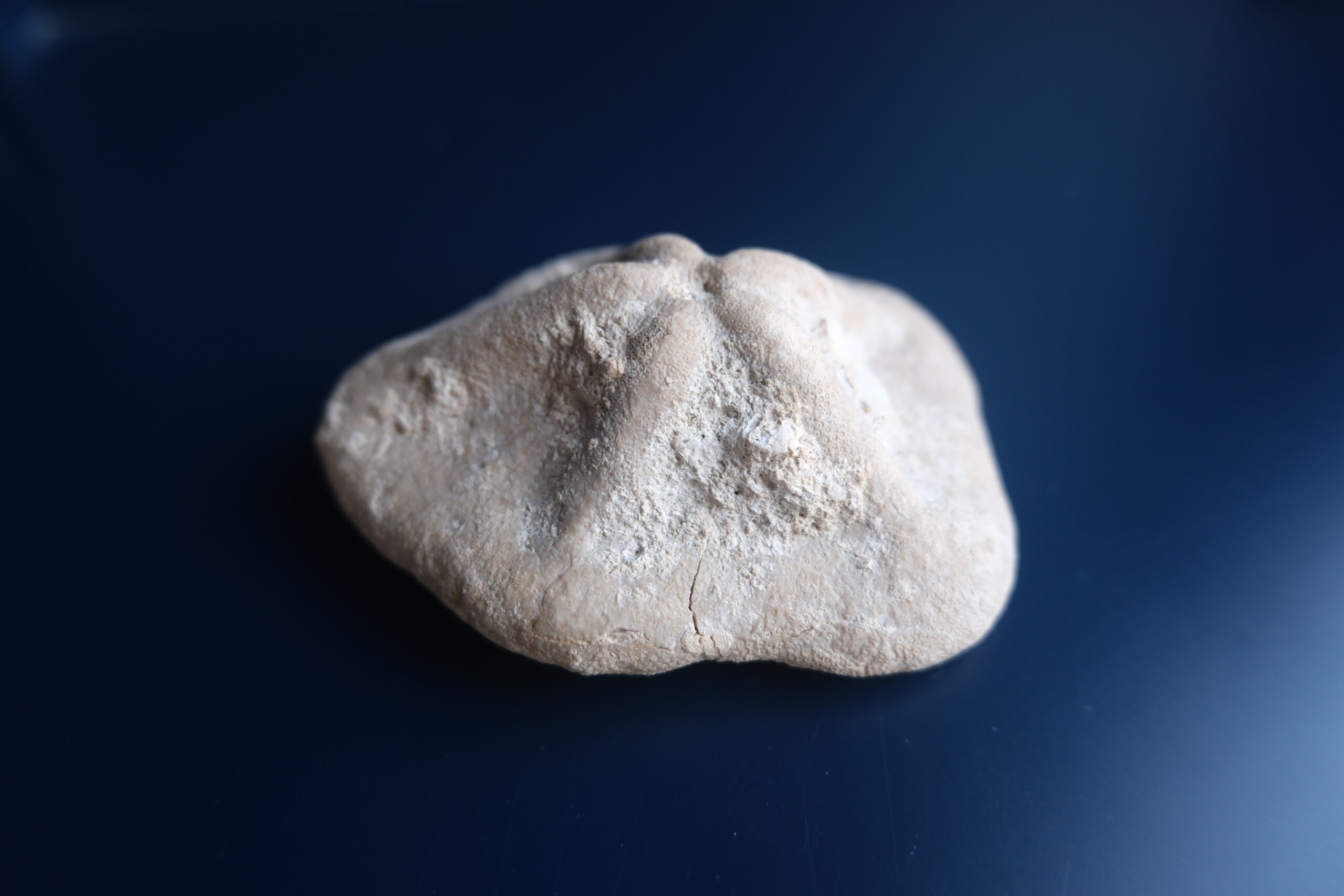

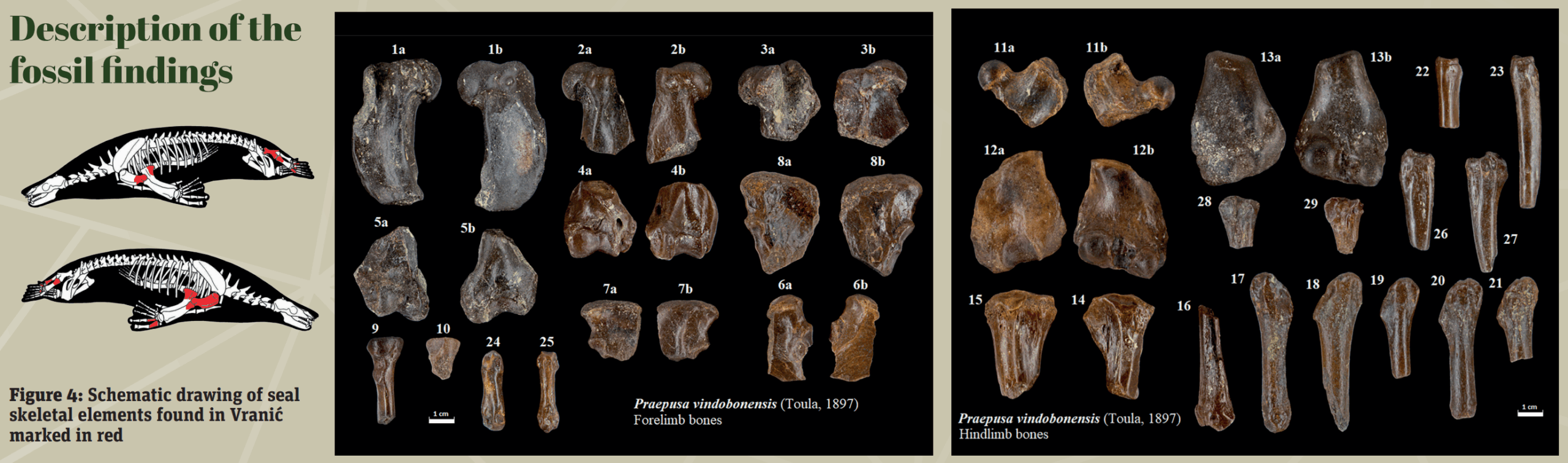

One of the most important fossil sites in the Papuk-area is the Vranić sandpit, located on the southern slopes of the Park. Numerous fossil remains have been discovered in the sandstone by researchers of animals that once lived in this vast inland sea, including whales, dolphins and seals.

In these fine-grained layers, there are also some marine mammal remains that possibly originate from the Pleistocene, when the climate changed and there was sudden melting of permafrost, causing a faster than usual sedimentation and burial.

On the lowest layers of the ground of this area, you’ll find ancient rocks from the Cambrian period, over ½ billion years old. These are partially covered by younger deposits from the Miocene when the Pannonian Sea still existed. As said earlier, a landslide has redeposited old rocks in fragments, mixed with debris (unit 1). In a later stage, marshes or smaller, shallow lakes formed on top of this debris, where finer sediments slowly settled (unit 2).

Fossil animals

Ostrea oyster fossil ⁕ ©2008 Manfred Heyde [Covered under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0-licence]

Oysters

Thanks to their sturdy and calcium-rich shells, several types of oysters have been preserved quite well, including Ostrea, Cubitostrea, Hotissa, and Crassostrea—all different species of oysters. These fossil oysters are usually found alongside corals and algae, but sometimes also in layers of densely packed shells, similar to what you might see along a shoreline. And because these fossils are found in the lowest few layers of the seabed, this tells us they were among the first species to settle in the Paratethys Sea as fossils.

Sea Urchins

Sea Urchins (or Echinoidea) had a hard and rounded calcium carbonate skeleton covered with spines. These lived just under the sea floor, and ate algae and organic material.

Limestones and marl layers from the Late Cretaceous and Miocene-periods sometimes reveal clusters of these fossilised inside them. This also suggests them living as groups.

Seal

In 2019, a large number of seal bones were found fossilised in quartz sand on the southern slopes of the Park. It was the first ever seal discovery in Croatia, and findings include 30 bone fragments: parts of flipper bones such the upper arm (humerus), forearm (radius, ulna), thigh bone (femur), shin bone (tibia), calf bone (fibula), and toe bones.

Bone measurements show that these remains match the species Praepusa vindobonensis, a small type of seal from the Early Sarmatian-period, with a body length of just over one meter. This species has unique features in the thigh and upper arm bones that make it different from other seals. It also had a relatively compact body and had adapted to live in the shallow waters of the Pannonian Sea.

It is unlikely that this seal lived near Papuk, but it is more probable that it died elsewhere during the Lower Sarmatian-period, and that its bones were transported by rivers that ended up in the river delta of what is Vranić today.

Whale

There are more findings in Vranić, like vertebrae and ribs of a small baleen whale—likely belonging to the Cetotherium-species, which typically was about 4-6 meters long, smaller than most modern baleen whales. Like whales today, the Cetotherium used so-called baleen plates to filter plankton and krill from the water. Its skull was relatively narrow and long, showing features that represent a transitional form between primitive whales and the modern species.

Dolphin

Unique is the finding of the oldest known fossil remains of dolphins—vertebrae, fin bones and teeth—which have been found right here, in the Papuk Nature Park. They belonged to a nowadays extinct family of toothed whales called Kentriodontidae. These dolphins lived during the Miocene and are considered early ancestors of the modern dolphins.

These fossils provide important evidence of how toothed whales/dolphins adapted to changing seas and climates in Europe during the Miocene. They show migration from warmer oceans and adaptation to brackish, shallow inland seas like the Pannonian Sea.

Shark

Even though there have not been discovered complete shark fossils, numerous single pieces of shark teeth have been found. Among the most impressive finds are Carcharocles megalodon-teeth, commonly referred to as Megalodon. This species was one of the largest and most powerful predators that have ever lived in the oceans—and lived between 3.6- and approximately 23 million years ago (Miocene and Pliocene). It is often regarded as an ancestor of the modern great white shark.

These sharks lived in warm, shallow seas and were at the top of the food chain (and still are)—carrying the name apex predators. The Megalodon is estimated to have reached lengths of up to 20 meters, and teeth measuring over 15 centimeters! These fossils are loved by collectors due to the impressive triangular teeth that were incredibly sharp to be able to tear apart large prey such as the three above ↑.

Due to changes in the climate and its food sources, the Megalodon eventually went extinct, possibly because its prey disappeared because of new competitors that emerged, such as orcas and toothed whales.

And besides teeth of this shark species, teeth of other shark species have been found too; including of the Hemipristis serra. This shark type also had sharp upper-jaw teeth to easily slice through prey, while its lower-jaw teeth were solely for getting a good grip on prey. It grew up to 6 meters long and lived in warm and shallow seas—but while it sounds cool that deadly sharks once lived here, as has been proven by these findings, it is entirely possible that these teeth have simply been displaced by the rivers leading to this area, sadly.

Coral

Besides marine animal fossils, a lot of corals were also found fossilised. These include so-called stony corals (or Scleractinia) and other coral types that lived in colonies. Mainly those second types are interesting, as they provide evidence that the Pannonian Sea was once a warm and shallow sea with stable conditions for large coral reefs to develop. These reefs probably had a significant role in keeping an ecological balance in the sea, as they provided both food and shelter for animals like molluscs, fish and sea urchins.

Rhino

While all of the above discoveries have been of sea animals, one more notable discovery was actually of a land animal—the rhinoceros, of which a lower jawbone has been found that likely dates back to the Miocene- or Pliocene epochs. It tells us there lived large land mammals somewhere nearby the Pannonian Sea on a stretch of land.

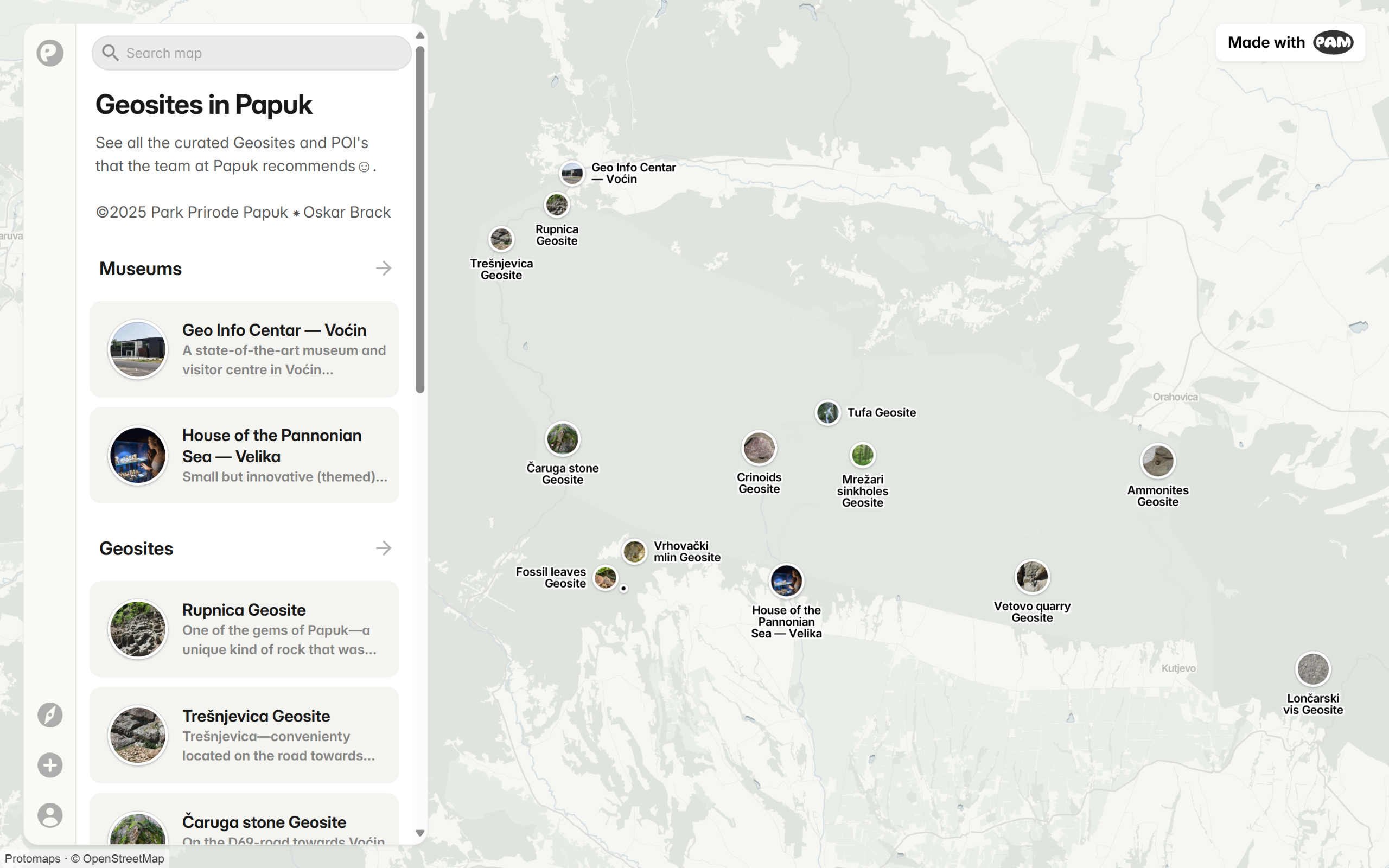

Sites that tell the story

Scattered across the Papuk UGGp, or Papuk UNESCO Global Geopark, are a variety of so-called Geosites that all shine a light on a geological phenomenon that shaped the Park to what it is today. You could e.g. walk over limestone layers that used to be the sea floor, see volcanic rocks that formed when this area was still volcanically active, or fossilised marine animals/echinoderms that lived very long ago, some upwards of ½ billion years ago.

Using the interactive map below, you can find the most interesting geosites in the Papuk UGGp for you. Each location has a detailed description of the sight, and highlights geologically unique features or rock formations. Use it to learn about the geosite before visiting, so you can make the most of your stay.

From Sea to Geopark

Papuk is actively committed to preserving the unique geological heritage of the Park. In areas like the Vranić sandpit, or other fossil sites, strict protection measures have been implemented to preserve the heritage as best as possible.

Under Article 111 of the Croatian Nature Protection Act (Official Gazette 80/2013), fossils are legally protected by considering them as natural elements. Collecting or moving of these fossils is therefore prohibited to preserve their original context, and must remain at their discovery sites. And in collaboration with UNESCO’s Geoparks programme, specific geosites such as Rupnica (Croatia’s first geological natural monument, protected since 1948) receive a legal protective status. Lastly, guided access to sensitive areas such as cave systems has been introduced, so access to these specific sites need to be coordinated with a guide or researcher in advance.

Furthermore, the Papuk Nature Park works closely with palaeontologists and geologists to uncover more of the Pannonian Sea’s past:

- Scientific research is actively supported.

- Fossil excavations and preservation are carried out carefully and recorded in databases.

- International collaboration with museums and/or research institutions help place discoveries into a broader context.

Educational programmes about the Pannonian Sea’s history are highly valued at the Papuk Nature Park. Visitor centres like the House of the Pannonian Sea feature reconstructions, fossils and interactive exhibits and offer guided school tours. On the trails scattered across the Park itself, information panels are placed on so-called educational trails and explain in detail how the Sea was formed, which animals lived there, and tell why it is important to preserve for future generations. Occasional workshops bridge the gap between the two above.

Papuk remains an important research site, still actively studied to get a clearer understanding on the Pannonian Sea, and the effect it had on the surrounding landscape. One of the goals of these protective measures is to keep the memory of this vanished sea alive.

Dive into The Sea

The Kuća Panonskog Mora—translated to House of the Pannonian Sea—is a small but modern visitor- and educational centre that tells the story of the vanished Pannonian Sea, but visually.

You’ll be welcomed by an engaging interactive presentation about the life on earth and how fossils are formed and preserved, followed by the findings that have been done in this area specific-ally to give you a glimpse into the ancient Pannonian Sea and the diverse plant and animal life that once lived there, long, long ago.

Exhibits showcase real fossils found in the area—including shells, snails, corals, whale vertebrae, shark teeth, fossilised leaves and even a rhino jawbone.

Outside, there’s an educational garden featuring a maze with a questionnaire, life-sized sculptures of prehistoric animals like a shark and a rhinoceros, that help to further explain the geological history of Papuk.

The centre offers a variety of educational programs tailored to diferent age groups—ranging from school children to adults; these include interactive lectures, hands-on workshops and fun educational games that deepen the understanding of the Pannonian Sea. The museum is located in the small village of Velika, the symbolic entrance to the Papuk UNESCO Global Geopark as its road continues into the Park.

Interested? To learn more and plan your visit, check out the official website: www.kucapanonskogmora.hr/